Frames of Mediality

By Morry Kolman

Today I want to think through some recent reading I’ve done with the help of my favorite videogame. I’m not sure how much I’ll get through, or how accurately I’m evaluating and conveying the ideas I’m working with, but trying to be excessively faithful to them without the help of other people to think about all of this has made me overthink this topic to the point of not being able to write it, so here goes.

A few weeks ago, I finished Shane Denson’s book Discorrelated Images. In it, Denson argues that new technological forms of creating, manipulating, and viewing images have changed the traditional relationships we humans have with the images around us. While before images were created with reference to human modes of perception (cameras functioned like eyes, scenes were easily parsable, film existed in the world the same way that humans do, etc.), they are now discorrelated from that relationship, their sensory affinities afloat, a consequence of existing in a messy morass of iPhones, I-frames, index fingers, the internet.

Denson discusses a number of forms of discorrelation, but I want to focus specifically on his second chapter, where he introduces two key concepts to his theory of images: dividuation, which he borrows from Gilles Deleuze, and mediality, which he borrows from Niklas Luhmann. Having very little background in either of these thinkers, this was a challenging chapter. The theory was thick, the definitional skirmishes dense, and I often found myself lost in a sea of terminology and canon that I had no business being in. What I did have, however, was a deep love of Super Smash Bros Melee, and the goal of this post is to explain these concepts through the bizzarely technical world of competitive videogame image processing.

Let’s start at the beginning, where Denson has his work cut out for him. He is claiming that our relationship to images has been fundamentally changed by their migration to a world of processes out of our hands. These processes and the images they create/enable carry in themselves new and often subperceptual instructions on how viewers ought to regard images and constitute their sense of subjectivity in concert with them. Skeptical theorists (he cites a few), will say that he is naively conflating observations about the new technicalities of image creation with the downstream creative practices that inform the content those images are used to carry (as his interlocutors analogize it, he is throwing away the difference between oil paint as substrate material and oil painting as a form)[1]. This would seem to limit the scope of his claim’s impact, as the human element of creating and consuming images hasn’t much changed. Point video camera, record actors, play back for audience; this could be in 35mm or an MP4 file, there’s no way the audience actually knows [2].

But lets turn the internal logic of the skeptic’s concepts around (here I am going to misconstrue the line of argument a bit for my own sake). If we’re going to think about the substrate of mediums as the material means of creating reproductions, then lets not orient ourselves to how they act to capture and preserve images (passive representation) but rather how they act to display them (active representation). And if we’re going to think about the form of oil paintings as the result of a particular practice of re-presenting, then lets not orient ourselves to the technicalities of the form (passive instruction) but rather the form of interpretation it invites from viewers (active instruction).

This is roughly (again, not being super faithful to the text here) what Denson is pointing out when he delves into the original meaning of the term “apparatus,” bringing up its constituent parts l’appareil and le dispotif to respectively denote the machinery for reproducing things and the “basic psychological, social, and ideological machinery that informs the spectator’s relationship” with the image [3]. With this view, the entire picture (so to speak) is much more active. This is a blessing and a curse: now that there are actions, we need actors. After we have recourse to YouTube videos and smartphones that wave away the short-sighted argument that changes in technological substrate are not related changes in orientation towards viewership and visual culture, we are left with a slew of unanswered questions. Who or what, exactly, acts to affect these changes? Maybe more importantly, where are they acting? And maybe most important of all, what are they even acting on? With the lines between technology, phenomenology, and subjectivity blurred, what is clear to Denson is that “the image, or the stuff of sensory experience, is… located on both sides of the divide – or is itself divided between them.” Thus prompting the question, “is it possible to locate dividuation itself – both the dividuation of the image and of experience – on both sides of the divide?” [4]

----------

Super Smash Bros Melee (or “Melee,” as its called by fans) is a popular children’s party/fighting game that came out in 2001 to promote the release of Nintendo’s then-latest console: the Nintendo Gamecube. It features a cast of 26 characters, ahead-of-its time graphics, and – most importantly for Nintendo at that moment – 4-way multiplayer. Produced under an extremely rushed timeline, Melee went from idea to disc in just 13 months, an action that proved a testament to the skills of Nintendo’s developers and put into the world a glitchy mess of a game that won the hearts and souls of players for years to come [5].

The Melee community stands out as one of the world’s longest-running esports fandoms. For 20 years, against all odds, it has persevered. 3 generations of consoles, sequel after sequel, active cease-and-desist campaigns from Nintendo, the silver-dollar-sized, button-mashing, clusterfuck-of-a-cultural-icon stands tall [6]. For the players, its steadfast imperviousness easy to explain: “Melee is sick.”

Allow me to translate: For the fans, nothing else feels the same, no other game has the technical and creative depth of Melee. It’s is a broken pile of code slapped together with the intention of its flaws being small enough that target demographic of 5-15 year olds opening their new console on Christmas morning could load up the disk and play without ever noticing them, and the fans wouldn’t have it any other way.

Let’s qualify a bit more and explains what it mean for the game to feel different. Speaking broadly, Melee runs at 60 frames per second with just 3 frames of input lag (each ~16.6ms). This means that if you push a button, the action linked to that button appears less than 0.05s later. With some moves activating on the first frame, players are at times literally strategizing faster than the console they are playing on. Additionally, somewhat unlike the other games in its franchise and noticeably unlike any other fighting game, the level of control you exercise over the actions and movement of your character in Melee is extraordinarily tight and precise. You can choose to grab your opponent now or in 1/10th of a second, you can hit them with the weak part of your leg or the strong part of your leg. Hell, with the right reflexes you can even choose which way you get hit. It is not unusual for top players to have APMs (actions per minute) in the 300-500 range, sometimes hitting literally dozens of buttons a second [7]. To illustrate, the video below is often referenced for showing the speed and precision at which the buttons on a controller can – and for competitive purposes must – be pushed. (TW for SA mention)

Melee is a game played microsecond-to-microsecond, a mix of human reaction, gut feel, and unmatchable flow state. Of course, all videogames require deep concentration and lightning-fast inputs to compete at the highest levels, but Melee is unique in its unrelentingness. There are no cutscenes, no small periods of reprieve as you watch an opponent blow up, and (normally) no teammates. Every game is you and your opponent, sprinting inexorably towards each other, frame after frame, none of your interactions not dictated by smaller ones. More than just a feeling of connection for the players, these microtemporal interactions create entertainment value at multiple levels of the viewing experience as well. There are so many things happening per second that there’s always some crazy interaction to appreciate; on the flip side, there are so many ways to play a character that a fan can always tell who’s behind the controller.

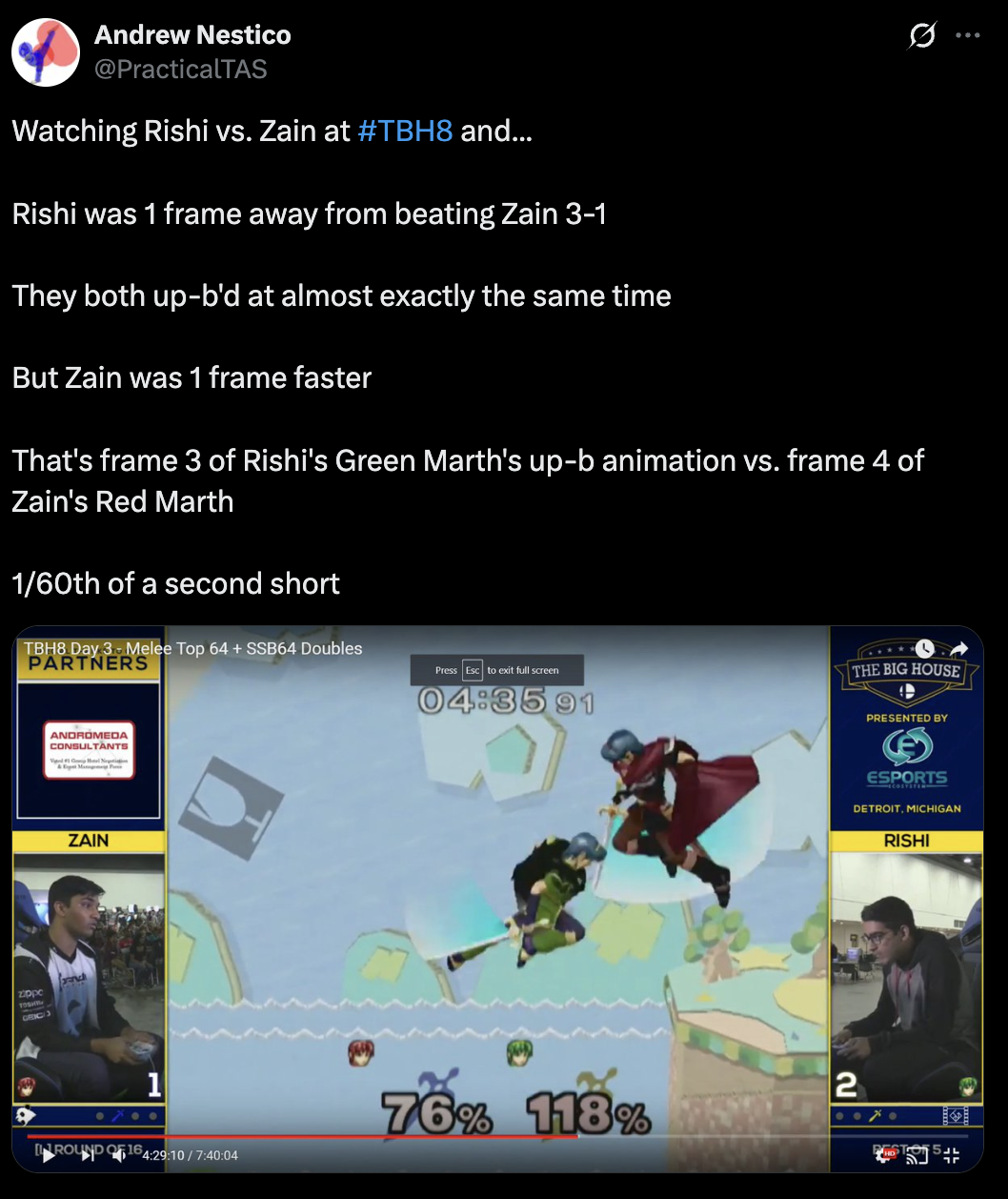

Fig 3. Hall-of-Fame level Twitter interaction. Zain is currently #1 in the world.

Fig 3. Hall-of-Fame level Twitter interaction. Zain is currently #1 in the world.

All this is to say that the experience of Melee rhymes with the way Denson elucidates the pre-perceptual forces of dividuation, “not measured by the spectator but immediately felt as an intensity. Accordingly, movement is apprehended not in terms of a clearly individuated form or object, but as a more diffuse or dividual force.” Melee’s intensity, however, is threatened every day by seemingly innocuous force: LCD screens. Or, more generally, the hegemony of digital video.

----------

Having set up his argument for not isolating control over the experience of the image on one side or another of the technological/processual divide, Denson turns to the glitch as a way to think through the ways these theoretically inaccessible substrates can affect visual experience and habituate us to new ways of regarding images. Glitches are perfect for this because they are at once (a) recognizable (b) pretty ubiquitous (c) meant to be ignored and (d) fleeting and temporary. They pop up when files fail, or the buffer for a video has run out, and are waved away as definitionally irrelevant to the actual content that is being shown. But quoting Jordan Schonig, Denson argues that “as conspicuous errors of this normally invisible process, compression glitches make the codec’s intelligent sorting of motion momentarily visible…[They] make us see the qualities and forms of cinematic motion as distinct from the people, things, actions, and events that such movements comprise” [8]. Whereas a reel of film jammed in a projector might still show us a skewed picture of its scene, a glitch in an MP4 file reveals to the viewer that the image is in fact not an image at all, but rather an array of information that we rely on computers to interpret and display.

That said, these blocky ephemera are easy to watch through, and indeed on any one instance might not even register to the viewer. It is here that above quote about the spectator not measuring these events as perceptual moments but immediately feeling them as an intensity finds its original context. Their importance is not in their individual occurrence, but the dividual dynamic they put on display as (again quoting Schonig) “functionally invisible – and yet undeniably visual phenomena” [9]. Thus Denson now holds in his hands at least once example of how the technological substrate of representation can make itself visible to the viewer. The dividuated image exists – in at least one form – and now it is time to pry this idea open further.

In order to the avoid a debate he sees Schonig getting mired in around concerns like “well how much affective power do we really give the substrate given that movies are still movies” and “is it overstepping to go from glitches to sketching an entirely new phenomenological account of digital video” (butchering here), Denson reaches the inflection point of the chapter – and of this blog post – by introducing the concept of mediality [10]. This concept, introduced by Luhmann, is needed to cement the dividuation of images as a constitutive force of media rather than an occasional breaking point. It encourages us to think of a medium not in terms of the particulars that comprise it but the interplay that it arises from, the “relation between some substrate and the forms that can be constituted out of it.”

What the fuck is that supposed to mean?

----------

Back to Melee: here’s a photo of a tournament from 2019:

Notice anything weird? The entire tournament, thousands of matches, are all played on old school CRT televisions. Why? Why would the community go through all the work of finding these TVs nobody wants anymore, lug them from tournament to tournament, and stake their competition on tech that is literally from the last century? To avoid a few milliseconds of lag, of course.

You see, Melee players are used to a very specific microtemporal relationship to their game. When they press a button it takes about 50 milliseconds (50ms/0.05s) for that action to be processed by the game and sent out for display on the TV. For analog TVs like CRTs the process to display that signal is effectively instantaneous. Digital monitors, however, can take anywhere from 2-150ms (or 0.002-0.15s) to go from signal to display [11]. As a competitive community that grew up only playing on CRTs and has habituated itself to those timings, these infinitesimal delays are unacceptable.

I know I talked about how fast Melee is played a bit earlier, but I think it’s worth talking about the different ways it can be fast as they relate to the visual experience. Each execution of Melee’s huge library of techniques (“tech”) can be broadly construed as existing on some spectrum between being a series of completely standardized muscle-memory inputs, and on-the-fly mix-ups or reactions. For example: “wavedashing,” the process of jumping into the air and performing a dodge back into the ground to scoot backwards or forwards, has a set timing to be performed perfectly; on the other hand, “powershielding,” the technique of activating your shield right before you are hit with a projectile to reflect it back at your opponent, is completely dependent on timing your input by tracking that projectile across the screen, and can have a success window as small as ~30ms (0.03s).

Fig 5. A series of wavedashes. As an aside: you can see that when performed perfectly, the character never even leaves the ground. This is because the character state that allows you to airdodge activates when the character is still in the squatting (or “jumpsquat”) part of their jump animation.

Fig 5. A series of wavedashes. As an aside: you can see that when performed perfectly, the character never even leaves the ground. This is because the character state that allows you to airdodge activates when the character is still in the squatting (or “jumpsquat”) part of their jump animation.

Fig 6. Pikachu powershielding Samus’ projectile.

Fig 6. Pikachu powershielding Samus’ projectile.

The fractions of fractions of a second are what define the competitive metagame – or “meta” – of Melee, the ever-evolving dance of strategy and skill players use to garner an advantage (this has been previously commented on by Stephanie Boluk and Patrick LeMieux) [12]. The granularity of control that Melee gives its players and the pace at which it lets them execute that control results in an infinite amount of creative variability available in the game.

Here are two gifs of a player executing almost the exact same set of moves (down air, shine, then neutral air or back air) at two completely different timings and angles: late and in front of the shielding Captain Falcon, or early and above then behind him. This may look seem like nothing, but everything done in these clips can be completely thrown off by a few frames of lag. The first Falco might mistime their down air and get grabbed, the second might not realize the Captain Falcon already jumped out of their shield. Whether or not this makes any difference is completely dependent on who is playing, how they choose to do it, and if they do it right.

Fig 7a. Dash, shorthop, late (low) down air on shield, L-cancel, shine, shorthop, fadeaway neutral air.

Fig 7a. Dash, shorthop, late (low) down air on shield, L-cancel, shine, shorthop, fadeaway neutral air.

Fig 7b. Dash, early (high) cross-up down air, L-cancel, shine, shorthop, approaching back air.

Fig 7b. Dash, early (high) cross-up down air, L-cancel, shine, shorthop, approaching back air.

What is at stake in these two near-identical looking clips is the heart and soul of Melee: tiny microscale differences compounding on top of each other to create iconic combos, memorable games, archetypal playstyles, and legendary players. The arc of Melee history is written in 60ths of a second. Seen in this light, CRTs and the frames they preserve move “from a passive channel between fixed subjects and objects to become instead the site of affective attunements,” the expressions they enable equivalent to the myriad ways you can raise an eyebrow and the different lengths of sighs [13]. “In other words,” Denson writes, turning back to mediality, “it is precisely the subject (and its objects)…that is up for grabs at the intersection of substrate and form” [14].

The reason Denson was so desperate to get away from the debates over how much X medium affects Y process to create Z image is because they all had this implicit understanding of images as discrete things, when in reality they are temporal processes. The reason he brought in mediality, then, is because it is built for understanding our visual experience as the rhythms of substrate and form, rather than a series of individuated images. With Melee, I think we are now in a better position to understand how this concept is useful.

----------

Given what I have told you so far, I have some questions:

What, exactly, is a frame? Is it one of the 60 images that appear on the screen every second? If so, then is it just an image? If that’s the case, why are they defined in units of time? Where is it? Is it in the console as the last 60th of a second that’s currently being processed by the game? Or is it the relic on the screen showing us what we did a 20th of a second ago? Hell, when is it? Is it now? The thing that I am seeing in the present moment? Or is it the image my actions will affect in the future? Are you finding these questions limiting? Ignorant? Naive? Do you wish you had a way to talk about frames without being bound by the demands of a static image?

If you want to punch me, then we seem to have found a use for mediality.

Mediality posits that the distinction between substrate and form is purely organizational: “a substrate consists of a ‘loose coupling’ of elements, a relatively chaotic or unordered mass of particles, while forms emerge out of the substrate as ‘tight’ or strict couplings or combinations of the same elements” [15]. This allows us not only to think about forms of media through different dynamics of coupling, but also allows us to think of forms themselves recursively becoming a “higher-order substrate for other forms” [16]; just as particles of air can be combined in waves to make notes, notes can be organized to make songs, songs to albums, albums to genres, and so on.

Conceiving of Melee’s images not as individual objects but as the result of a “coupling” or organization gives them the temporal quality we’ve been looking for, the measure of which is the length of the process involved in putting all the game’s constituent parts together to create the experience of their forms, “which emerge from and return back into a substratal pool of disarticulation” [17] Finger movements, signal fires, transistor switches, phosphor illuminations, they all come to mean something together in the assembly of a frame: a dividuated image dispersed across a number of elements technological and biological in nature, whose parts are oriented towards one another through the way they are coupled to create the next ~16 milliseconds.

----------

Denson takes this “images are temporal” argument much further and talks about the consequences of discorrelation with a bunch of stuff about control, subjectivity, and Deleuze. At least for now I am not really interested in going down that route. My goal was to explain how you might understand what Denson means by the terms dividuation and mediality through Melee, and I think I have done that.

That said, like the images I’ve been discussing, my account of Melee is made up of a number of elements I have coupled together to make a post. There are many other elements to talk about, and many other ways to organize them. You can choose to stop reading now if you’d like, but partially as notes for myself, partially as avenues for the reader who might want to think more about this, and partially for every Melee nerd who will yell at me about Slippi, BenQ monitors, and input lag, I want to end with a list of all the directions I did not take this write-up:

First: All of the research involved in this piece is from grassroots figures in the scene doing their own experiments and disseminating them to the community. This is a testament in itself, but the more notable thing related to that is that the average floor of technical understanding in the Melee community is uniquely high. That is, if you take media literacy to mean understanding the conditions of media that you consume and the proper ways to interact with them, the Melee community is a model for breadth of education as a result of its emphatic focus on the technical conditions of its play. You either play Melee on a CRT because you know that’s how the signal is standardized, or you emulate it on a computer and adjust the settings so that it displays the same way a CRT does.

Second: Speaking of that emulation adjustment, I did not even TOUCH the other side of this entire coin: emulating the game on a computer (rather than plugging a console into a monitor) actually has less lag than a CRT. However, CRTs are still the standard, so in order to get back to familiar timing, players have to actually add back in about 2 frames of lag.

Third: Currently, in-person tournaments are obviously impossible, and the community has largely relied on (again, completely grassroots) a network program called Slippi to keep the competitive scene alive. Slippi adds another layer of complexity to the organizational dynamics of frames because it uses “rollback.” Given that sending inputs back and forth to each other over the internet takes a few ms, rollback smooths out online gameplay by assuming that not much will change in 2-3 frames (eg. if you’re running left, you’ll probably still be running left in 0.05s), and lets you play against the 2-3 frame prediction of what your opponent will do. Once it gets the actual data from your opponent, it re-emulates the game to the present frame, correcting any mistaken assumption it made. 99.9% of the time nothing happens, so it’s embraced as a revolutionary way to get closer to the feeling of IRL gaming without worrying about internet lag. That said, now we also have to add predictive computing to the mix of what makes a frame, which Denson actually talks about, even briefly bringing up rollback netcode as an exemplary aside.

Fourth: Given all of the above, the title of the tournament series “See Me On LAN” is deserving of a deep reading.

Fig 9. See Me On LAN CRT Logo

Fig 9. See Me On LAN CRT Logo

Fifth: Denson actually has a bunch of stuff specifically about CRTs in the chapter. It’s interesting and there for the curious, but I thought it would probably distract from the main point. I didn’t want to get into progressive scan vs interlacing etc.

Sixth: There is an entire book to be written about the Melee community’s attitude towards its technological dependencies and what you could narrativize as a decade-long mod push to fix and democratize the most “authentic” melee experience in the face of arbitrary technical barriers that are holding it back. Looking at you arduinos, notching, 2 frame smash turns, polling fix, the b0xx, UCF, etc.

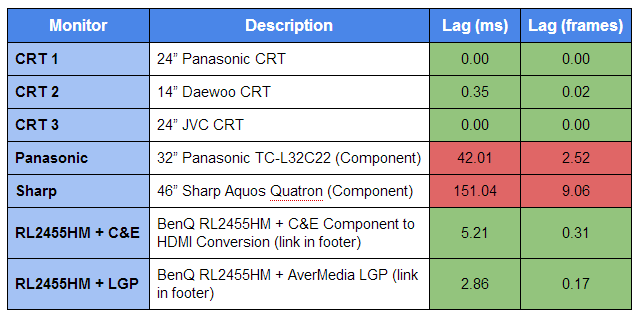

Seventh: Theoretically, monitors like those from BenQ and other high-end gaming-focused manufacturers are fast enough to serve as a reliable substitute for CRTs, but this requires a big up-front cost of monitors and digital-to-analog converters for smaller venues whose weekly attendees can normally be relied on to bring their own CRTs for a discount on entry fee. In line with the upwards-cascading dynamic of microscale choices causing macroscale changes we kept seeing, this makes it harder for bigger one-off (“major”) events with economics to justify ditching CRTs to make the switch, as the lower-level events significantly shape the community norms. I also like that this chart presents frames as a unit of time.

Fig 10. A chart of display lag.

Fig 10. A chart of display lag.

Eighth: Related to the viability of those higher-end monitors, it’s always funny to look at the CRT v. Monitor debate. It’s a great case of empirical data not being able to overcome an affective semiotic force. Whether or not the delay of LCD monitors is objectively so low as to be negligible when compared to CRTs, two of the major accounts of display lag (both of which contribute to this post) mention the impossibility of ever creating a test that gets around the fact that CRTs and LCDs just look different, and so any methodology will always give way to the conscious and unconscious bias players have towards CRTs. I guess this problem makes sense, you can’t have a blind study for a visual medium.

Fig 11. David “Kadano” Schmid explaining the problems with CRT/LCD testing.

Fig 11. David “Kadano” Schmid explaining the problems with CRT/LCD testing.

Figure 12: Jason “Fizzi” Laferriere complaining about the symbolic force of CRTs.

Figure 12: Jason “Fizzi” Laferriere complaining about the symbolic force of CRTs.

Ninth: As mentioned, Melee is a very glitchy game, to the point where some glitches (like wavedashing) are used every second of play. The community debate about what counts as a glitch, what glitches are acceptable, what glitches are unacceptable, and what things aren’t glitches but should clearly be dealt with is a thorny mess of nostalgia, prescriptivism, and salty players. It’s very interesting, and the discussion of “rules vs. laws” in this popular explainer for the uninitiated-to-Melee audience below is a good way to wade into it if you want to. Perhaps more importantly, I think there’s a ton to be thought about with regard to how this makes the community aware of themselves and their gameplay as a sort of glitch in the sense of Schonig. This (and the modding and media literacy points above) is probably an avenue into a discussion as Melee as a site of resistance to the Deleuzian control society stuff that Denson brings up later in the chapter: a community that was never supposed to exist, playing the game in a way it was never supposed to be played, on tech that is supposed to be outdated, modifying it in ways the IP owner vehemently tries to shut down. The images of the game may be dividuated, but they are dividuated on their terms.

Lastly: I have no point to make here, but I love the garbage-disposal-vaporwave-neon aesthetics of Melee research. Here are two examples from the two accounts of lag discussed above.

Fig 14. GIF of lag test by Fizzi.

Fig 14. GIF of lag test by Fizzi.

Note: Thanks to Ambisinister and Metonym for helping me with some technical questions around CRTs, emulation, and lag of all sorts.

Citations:

[1] Shane Denson, Discorrelated Images, Duke Press, 2020. p52.

[2] Denson, p54.

[3] Denson, p55.

[4] Denson, p56.

[5] Richard George, IGN, May 4 2012, https://www.ign.com/articles/2010/12/09/super-smash-bros-creator-melee-the-sharpest

[6] Austin Ryan, InvenGlobal, December 15 2020, https://www.invenglobal.com/articles/12898/nintendos-battle-against-the-super-smash-bros-community-can-change-the-industry

[7] Avery “Ginger” Wilson, May 30 2020, https://twitter.com/SsbmGinger/status/1266841917758808066

[8] Denson, p57.

[9] Denson, p61.

[10] Denson, p63.

[11] Jason “Fizzi” Laferriere, MeleeItOnMe, March 2014, http://www.meleeitonme.com/this-tv-lags-a-guide-on-input-and-display-lag/

[12] Stephanie Boluk and Patrick LeMieux, Metagaming, University of Minnesota Press, 2017. https://manifold.umn.edu/projects/metagaming

[13] Denson, p66.

[14] Denson, p65.

[15] Denson, p64.

[16] Denson, p64.

[17] Denson, p66.

Figures:

Figure 1: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NEco8hbasbI

Figure 2: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vXgpGBbh5r8

Figure 3: https://twitter.com/ZainNaghmi/status/1060980925729771522

Figure 4: Matthew Healey for The Grafton News, https://www.thegraftonnews.com/entertainmentlife/20190829/soul-of-game-inside-wild-world-of-esports-at-dcu-center

Figure 5: https://liquipedia.net/smash/Wavedash

Figure 6: https://www.reddit.com/r/smashbros/comments/1pw14h/powershield/

Figures 7a and 7b: https://aminoapps.com/c/smash/page/blog/ssbm-falcos-options-on-shield-2-after-the-shine/Jnfd_uPX0qZ8NVnaVlelRGbrnb1NR7

Figure 8: https://twitter.com/PracticalTAS/status/1049440650926727168

Figure 9: https://smash.gg/tournament/see-me-on-lan-8/details

Figure 10: http://www.meleeitonme.com/this-tv-lags-a-guide-on-input-and-display-lag/

Figure 11: https://twitter.com/Kadano/status/1113231872346284032

Figure 12: See Figure 10.

Figure 13: https://youtu.be/8qxVDOc-oV8?t=286

Figure 14: See Figure 10

Figure 15: See Figure 11.